*A translated Italian version of this interview was published in the October issue of Economy, and is also available on Economy’s website.

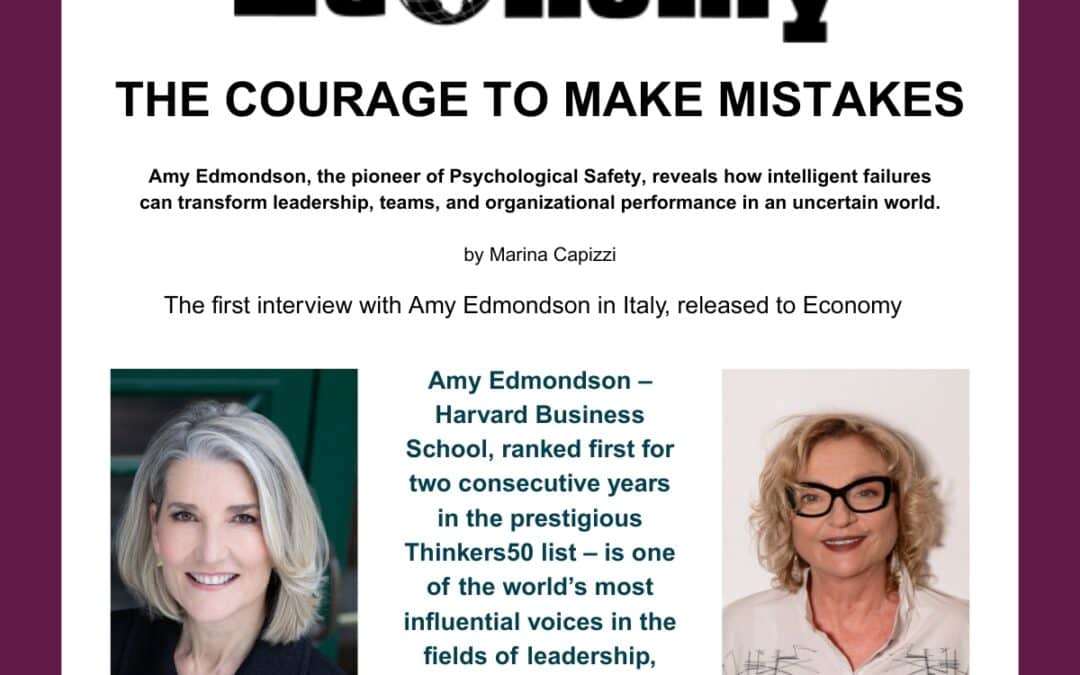

Amy Edmondson is a professor of leadership and management at Harvard Business School. She has ranked n#1 twice in a row on the prestigious Thinkers50 list. In short, she is one of the world’s most influential voices in the fields of leadership, organizational learning and team performance. I have met her recently to present her two books, translated into more than 20 languages: Organizzazioni Senza Paura e Il Giusto Errore, the latter recognized by the Financial Times as the best business book of the year. This is her first interview in Italy.

Professor Edmondson, with your book, The Fearless Organization you have spread Psychological Safety across the world. Can you tell us what Psychological Safety is and is not, and what happens when it is present or absent?

Psychological Safety is the belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes. Beware: safe does not mean comfortable, cozy, happy or free from effort. In a psychologically safe environment, people tend to be energized; they share ideas, doubts, mistakes and learn from them. This can make the difference. Instead, when people don’t have Psych Safety, they are uncomfortable speaking up with bad news or the problems or requests for help, hide mistakes, never disagree with the boss even when the boss might be wrong. In this workplace, the culture of silence — a general belief that speaking up isn’t welcome — dominates. And it has a very high concrete cost: people feel that their voices cannot be heard, even at critical moments.

For many people, the term “psychological” does not feel concrete enough to justify a real investment. Why should an organization invest in Psych Safety?

You should invest in Psychological Safety because it’s a strategic asset in an uncertain world. When you can set a plan, ask people to follow it, monitor it precisely, you have less need for Psych Safety. However, if you depend on innovation — if the people in your organization must work together to solve problems and to create new solutions in an uncertain context — then Psychological Safety is a major determinant of your ultimate performance. There is a strong relationship between Psych Safety and performance.

How can leaders build Psychological Safety and shift their teams’ mindset around risks and failures?

Leaders have the responsibility to create the conditions whereby others can show up and bring their voices, ideas, and skills to contribute. Psychological Safety is an emergent climate property, but it does not take years to show up. The more leaders engage in learning behaviors, the more they and the group will experience Psych Safety. And the more Psych Safety, the more people are engaged in learning behaviors. Even if you are not a leader, you can influence Psychological Safety by asking good questions and listening to your peers and colleagues.

In recent decades, starting with the “war for talent”, companies have focused on individual talent, but today performance increasingly relies on teams. Psychological Safety is a team sport. Can it help teams become more autonomous and help leaders foster that autonomy?

You can hire very smart people, but talent does not directly translate into performance — except for purely individual jobs. If you focus on talent as an individual-level phenomenon, people want to compete rather than collaborate. They want to win the contest. And that is not helpful when the work is interconnected and collaborative. We do have to reframe this whole picture. The crucial ability is a combination of learning and connecting with others in a meaningful way, and then seeing the third thing that lives between us that could be created together. We must train our brains to see that the value lies in the connections between us, not in the individuals themselves. Psych Safety plays an important role in that.

With your book Right Kind of Wrong, you return to a topic that is very important to you: the role of the approach to errors in organizational learning and the relationship between high team performance and error rates…

Yes, this has been a very important topic for me since the beginning of my career, when — during research in a hospital setting — I discovered that better teams had higher error rates, not lower. The better teams do not make more mistakes; they are simply more willing to report them and learn from them.

This is a very timely book because we live in an era where failures are celebrated, yet in organizations the expectation is still zero mistakes. Your book introduces the science of failing well, showing that it all starts with the ability to distinguish different kinds of failure and handle them productively. Could you tell us more about this?

You are right — nowadays it is trendy to celebrate failure, and at the same time most people still do not accept mistakes. If you really want to succeed at the highest level, you have to tolerate a lot of failures along the way to that success. The right question is: under what conditions does it make sense to fail? To answer that, we must distinguish between mistakes and failures. I talk about basic mistakes and complex or intelligent failures. A basic mistake is an unintended deviation from existing policy or practice. It is preventable, and we should prevent it. A failure is a non-preventable result. A complex failure depends partly on you and partly on the context, and we must prevent it by picking up weak signals and using the available information about the context. An intelligent failure is an undesired result in new territory, where we are pursuing a goal and we have just a hypothesis or good reasons to believe it might work. We cannot have innovation without intelligent failures. The only failures we should learn to love and seek more of are intelligent failures.

In this book, you highlight contextual awareness as a key skill for dealing with failures. What does it mean and why does it matter?

The two dimensions that help us better understand the context are the stakes and uncertainty. So, the question is: what are the stakes and how much uncertainty is there? When the risks are high and the uncertainty is low, careful attention to detail is the right way to go. But when the stakes are high and the uncertainty is high you have to find ways to experiment in small, safe ways despite that context.

We always talk about self-awareness, but never about contextual awareness…

Yes, there is plenty written about self-awareness, but situational awareness is also a crucial part. By being context-aware, we open up more skills and more responses that suit the context in a thoughtful way. We will naturally do some of the right leadership behaviors because we force ourselves to be context aware. This is important for having effective leaders and colleagues.

Thank you, Professor Edmondson, for your books – a true source of inspiration.

by Marina Capizzi

PRIMATE co-founder